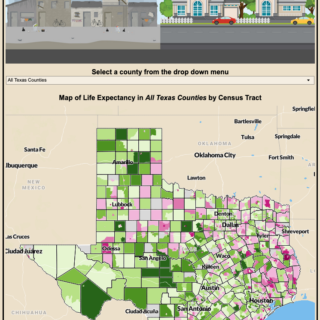

The analysis found that Texans who live in low-income neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, low education levels, and large minority populations live significantly shorter lives compared to those who live in communities with high incomes, low poverty rates, high education levels, and large White populations. EHF’s interactive mapping tool shows life expectancy rates for more than 4,700 neighborhoods at the census-tract level for all Texas counties.

“Drive 15 minutes through the biggest counties in Texas and you can go from a neighborhood where people usually live more than 85 years to another where the average person dies before he or she is 65,” says Elena Marks, president and CEO of the Episcopal Health Foundation. “These numbers should spark important conversations across the state on how we can all take action to address the non-medical, root causes of these dramatic differences in health.”

EHF’s analysis found that across all Texas neighborhoods, the median life expectancy is 77.8 years. The numbers show an 11-year gap between the life expectancy in the bottom 5% of neighborhoods (72.1 years) and the top 5% (83.3 years). The gap between the top and bottom 1% of Texas neighborhoods in life expectancy rates widens to nearly 17 years.

Researchers found that in the neighborhoods with the lowest life expectancy 27% of residents lived below the federal poverty rate, while only 11% of people living in highest life expectancy neighborhoods had incomes below the poverty rate. In addition, 65% of households in the lowest life expectancy neighborhoods had annual incomes below $50,000, while two-thirds of households in the neighborhoods with the highest life expectancy had incomes above $50,000.

When it comes to race and ethnicity, the group of neighborhoods with the highest life expectancy had populations that were 53% White, 31% Hispanic and 7% Black. In contrast, the population of neighborhoods with the shortest life expectancy rates were 35% White, 40% Hispanic and 22% Black.

The analysis also found a high correlation between education levels and life expectancy in Texas. More than 40% of adult Texans in the highest life expectancy neighborhoods had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Only 12% of residents in the group of neighborhoods with the lowest life expectancy had a college degree or higher.

“We know that 80% of what determines a person’s health doesn’t involve access to medical care, it’s about income, housing, community safety and more,” Marks said. “These life expectancy numbers are further evidence that to improve Texans’ health and quality of life, we have to focus on the underlying causes of poor health that have nothing to do with going to a doctor or hospital. We have to change the conversation to improving health, not just healthcare in Texas.”

EHF’s analysis looked at the life expectancy estimates from the National Center for Health Statistics for 4,709 census tracts across Texas. Those estimates were determined using six years of mortality and population data.