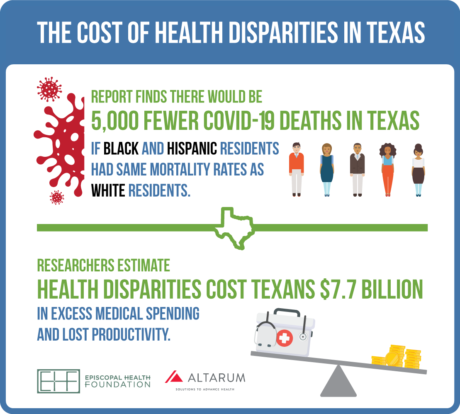

Report finds there would be 5,000 fewer COVID-19 deaths if Black and Hispanic residents in Texas had same mortality rates as White residents

Researchers estimate health disparities cost Texans

$7.7 billion in excess medical spending and lost productivity

HOUSTON – Significant pre-existing health differences for Black and Hispanic residents in Texas are leading to higher COVID-19 death rates, plus billions of dollars of increased health care spending and lost work productivity. Those are some of the findings of an updated 2020 study led by researchers at Altarum examining the economic burden associated with health disparities across the state during the pandemic. Episcopal Health Foundation sponsored the report.

The report estimates that if Black and Hispanic residents in Texas had the same COVID-19 mortality rates as White residents, there would have been 5,000 fewer deaths as of the end of September 2020, and the number of total deaths in Texas would be reduced by 30% (16,000 to 11,000). Researchers also found that if Black and Hispanic Texans were hospitalized at same rates as White residents in Texas, there would have been 24,000 fewer hospitalizations across the state. Those hospital stays represent more than $550 million in health care spending.

“These numbers are a glaring reminder of how non-medical factors like economic status and living conditions impact health and how COVID-19 is highlighting that in the worst way,” said Elena Marks, president and CEO of the Episcopal Health Foundation. “The human and economic costs of health disparities continue to grow during the pandemic and we’re learning why we can’t address them through medicine alone. Something has to change in Texas.”

The report noted that people of color in Texas are more likely to work in front-line service jobs, live in crowded and multi-generational housing, rely on public transportation, have underlying health conditions like diabetes and obesity, and lack health insurance. These factors contribute to Black and Hispanic residents in Texas being more likely to contract COVID-19, and when they do, being more likely to have a serious case that requires a stay in the hospital or leads to death.

Researchers say the report shows how social determinants of health have economic costs as well as human costs. The report estimates that during 2020, disparities in health by race/ethnicity cost families, employers, insurers, and governments an estimated $2.7 billion in excess medical spending and another $5 billion in lost productivity. Researchers say that’s a 60% increase in excess medical spending and a 72% increase in lost productivity from similar estimates in 2016.

“The current COVID-19 pandemic is raising the stakes and the visibility of health disparities in Texas and throughout the country,” said Ani Turner, co-author of the report and director of Sustainable Health Spending Strategies at Altarum.

Turner and the other researchers estimate by 2030, the economic costs of health disparities in Texas are expected to increase again to $3.4 billion in excess medical spending, $6.1 billion in lost productivity, and 551,000 lost life years at a value of $28 billion.

Marks says expanding Medicaid would ensure that uninsured, low-income Texans would gain access to needed health insurance to access care, and ultimately have better health outcomes. But she says health coverage isn’t enough.

“These health disparities are preventable, and we can change millions of lives if we invest our health dollars in new ways,” Marks said. “COVID-19 has shown us to really improve health we have to address non-medical factors like unhealthy housing conditions, air quality, education, employment, affordable healthy foods, and safe places to exercise. If elected officials, policymakers, and communities don’t change their priorities, the vicious cycle of health disparities only will get worse.”

The report was co-authored by Ani Turner of Altarum, Patrick Richard of the Uniformed Services University, Thomas A. LaVeist of Tulane University, and Darrell J. Gaskin of Johns Hopkins University.

For more information or to schedule an interview, please contact Brian Sasser, EHF’s chief communications officer, at 832-795-9404 or bsasser@episcopalhealth.org